ABOVE: © ISTOCK.COM, FOREMNIAKOWSKI

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US, officials focused limited testing capacity on symptomatic people who had recently traveled to or been in close contact with someone who had traveled to places with confirmed outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2. A year later, it’s clear that some proportion of viral transmission—perhaps as high as 50 percent—comes from presymptomatic or asymptomatic individuals, making it difficult to trace transmission. In a study published in Clinical Infectious Diseases June 15, researchers analyzed blood collected between January 2 and March 18, 2020, and found antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in samples from nine people in five US states, meaning that the virus was likely present in the US in late 2019.

“We suspected that there were probably cases that preceded the ones that were diagnosed and confirmed. This is very suggestive that there were probably multiple exposures prior to...

In 2018, researchers at the National Institutes of Health and their collaborators across the US started recruiting volunteers for the All of Us research program—the aim of which is to collect individualized health data from lots of people over many years with the ultimate goal of making medicine more individualized. The study was therefore trekking along, gathering participants’ medical history and blood samples across the US in early 2020 when SARS-CoV-2 showed up.

As public health shutdowns started and recruitment and testing for longitudinal studies paused, Keri Althoff, an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and her colleagues on the All of Us team talked about if they could look in previously collected specimens to see whether or not there were antibodies present that would target SARS-CoV-2. This line of investigation could “help us put together the puzzle about the early days, because that can help us understand where we can improve upon for preparedness for future outbreaks,” she says.

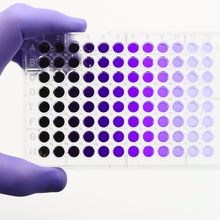

Researchers across the country were simultaneously developing tests to detect these antibodies, so the All of Us team created a partnership with a group at Quest Diagnostics and sent samples to their clinical lab for antibody testing. They requested two tests for each sample: one for antibodies that target the protein that surrounds the SARS-CoV-2 genome and one for antibodies that target the viral spike protein. Out of the 24,079 people who gave blood specimens between January 2 and March 18, 2020, 147 were positive for antibodies directed toward the nucleocapsid. Just nine participants tested positive for antibodies on both tests.

The earliest positive sample—from a participant in Illinois taken on January 7—was collected more than two weeks before the first official case report in the state on January 24. The researchers also found SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in people from Massachusetts, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Mississippi in samples collected before these states had official cases.

“On average, it takes about two weeks for [immunoglobulin G] antibodies to be detectable . . . so now we’re talking about a December 24 potential infection or sometime even prior to that,” explains Althoff. She adds that the results corroborate and extend findings from a November 2020 study led by researchers at the Centers for Disease Control that found SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in blood collected from donors in December 2019 and January 2020 in California, Connecticut, Iowa, Massachusetts, Michigan, Oregon, Rhode Island, Washington, and Wisconsin.

“That there were some cases of COVID-19 prior to the documented cases [is] a reasonable conclusion, based on the fact that it’s unlikely that we caught the very first case in many of these locations,” says Saahir Khan, a clinician-scientist at the University of California, Irvine, who did not participate in the work. Because the authors found a very small number of antibody-positive individuals in this relatively large sample that they tested, he adds, it’s possible that the number of antibody positives that they detected here are not true positives.

“When you have a situation where it’s a very low prevalence, false positives are something that you wrestle with,” acknowledges Althoff, but the sequential testing strategy of two positives, the subsequent quantification of the antibodies in those samples, and the simulation models that the researchers ran to predict healthcare use, cases, and deaths all indicate that it’s very unlikely that the results are due to error.

Other lines of evidence they could pursue in the future, according to St. John, are neutralization assays, in which researchers mix antibody-positive serum or antibodies isolated from blood samples with live virus and see what happens. As it is, the results are “very strongly suggestive, but a neutralization test would have just really sealed the deal for me,” she says.

As for what the results mean for the origins of SARS-CoV-2 in the US, “it’s important to remember this is a very small sampling of what’s happening in the country at that time,” St. John explains. “It could be many more infections than we anticipated,” she adds. “It’s a wake-up call in some sense that we need to improve our surveillance for detection of these types of emerging infectious diseases, so that we can catch more of the early cases, because it really emphasizes that we have a small view of what was happening.”

Interested in reading more?