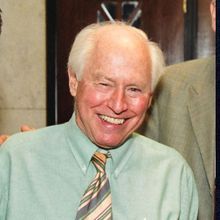

John Allan Hobson, a prominent sleep researcher and psychiatrist, died on July 7 at his Vermont home due to diabetes complications at the age of 88. His work contradicted prevailing hypotheses of the day on the meaning of dreams and set the stage for much of the work investigating the rapid eye movement (REM) phase of sleep.

According to Dream Life, his memoir, Hobson was born on June 3, 1933 in Hartford, Connecticut, where he remained for his childhood. He and his brother Bruce were raised by their father, a lawyer, and his mother, a homemaker. He attended high school at what is now known as Loomis Chaffee School, a preparatory school in nearby Windsor. He obtained a degree in 1955 from Wesleyan University and earned an MD at Harvard Medical School in 1959.

From there, he completed internships, fellowships,...

When Hobson’s interests shifted to sleep research, it wasn’t yet widely accepted as a scientific area of study. In the early 1960s, many academics thought that dreams represented veiled subconscious desires and that the content of dreams could be interpreted through psychoanalysis. His earliest work centered on physiological aspects of sleep, such as drops in heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration, along with research on cats to understand shifts in sleep cycles due to drug use or brainstem trauma.

See “Mysterious Brain Waves May Connect REM Sleep with Visual Experiences”

In 1977, Hobson published a landmark paper describing the neurological components of dreaming. Dreams weren’t, he wrote, a person’s innermost desires. Rather, he suggested, dreams were caused by random neurological impulses that the brain tries to make sense of. He asserted that this activity did contain information, just not anything that could be used for psychoanalysis. Later in life, he was for a time openly critical of psychoanalysis in general.

“I’m skeptical about any absolute set of rules, scientific rules, moral rules, behavioral rules,” Hobson told The Boston Globe in 2011. “That’s one reason why I don’t feel bad taking on Sigmund Freud. I think Sigmund Freud has become politically correct. Psychoanalysis has become the bible, and I think that’s crazy.”

Although he later conceded that psychoanalysis was useful for addressing certain conditions, he remained steadfast in his view that dream analysis wasn’t helpful, Hobson’s former colleague Ralph Lydic tells The New York Times.

See “Opinion: The Biological Function of Dreams”

In addition to coauthoring more than 200 papers throughout his career, Hobson penned 20 books, beginning with The Dreaming Brain in 1988. Most of the books were about the science of sleep and the complexion of chemical activity in the brain when conscious or not.

In 1965, Hobson bought a farm in Vermont and passionately cared for it, according to many online reports from family and friends. He was able to convert part of a barn into a sleep study classroom and museum and welcomed guests there. This exhibit honored the science of sleep but also celebrated artistic renditions of the brain. His family held a memorial at the farm three days after his death.

Hobson is survived by his wife, daughter, four sons, five stepchildren, and four grandchildren.

Interested in reading more?